I enjoyed The Painted Girls by Cathy Marie Buchanan so much that I’m kicking myself for not reading her first novel when it came out in 2009. The Day The Falls Stood Still was getting hype in 2010 from various reviews, and I had blogged that it was part of Canada Also Reads (an indie response to the lacklustre list of CBC’s Canada Reads that year).

The Painted Girls is heartrending, gripping novel set in belle époque Paris and inspired by the real-life model for Degas’s Little Dancer Aged 14 and by the era’s most famous criminal trials.

Following their father’s sudden death, the Van Goethem sisters find their lives upended. Without his wages, and with the small amount their laundress mother earns disappearing into the absinthe bottle, eviction seems imminent. With few options for work, Marie is dispatched to the Paris Opéra, where she will be trained to enter the famous Ballet and meet Edgar Degas. Her older sister, Antoinette, finds employment—and the love of a dangerous young man—as an extra in a stage adaptation of Émile Zola’s Naturalist masterpiece L’Assommoir.

Set at a moment of profound artistic, cultural, and societal change, The Painted Girls is a tale of two remarkable sisters rendered uniquely vulnerable to the darker impulses of “civilized society.

Something about historical fiction sucks me in completely, and Buchanan’s story flowed seamlessly through the pages. At times predictable, the plot dragged as history is never as fast-paced and gripping as fiction. The Painted Girls takes place in Paris, 1878, where the three Van Goethem sisters live in a squalid apartment in Montmarte.

Antoinette takes on the role of the provider when their father dies and their mother continually spends her wages as a laundress on absinthe. Antoinette is the “bad girl”—petty thief, falls for the bad boy, and has less educated language; Marie is the “good girl”—saviour of the family, all hopes rest on her shoulders; and Charlotte is the “spoiled brat”—too young to send to work, but treated like a little saint despite circumstances.

Antoinette, who was let go from the Paris Opera ballet school, brings her younger sister Marie there to train. She is taken on (for a mere seventeen francs a week) but dutifully takes on the role. Marie is dedicated to not end up like her mother or her sister, makes do with tattered hand-me-down ballet skirts from Antoinette, and spends countless hours working on her training.

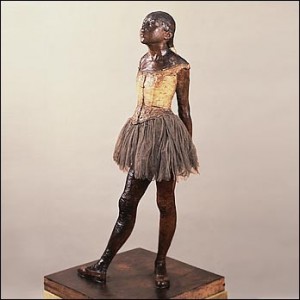

Edgar Degas’ sculpture A Little Dancer, Aged 14 cast in bronze (originally in wax) | source: National Gallery of Art (USA)

When Marie is seen by Degas and asked to model for his drawings and sculptures, she feels beautiful and justified for her dedication to the ballet and life as a ‘petit rat’. Slowly though, Antoinette slips further from her family and duties, lustfully following Emile Abadie, a street youth who makes her feel “adored”. Soon, Antoinette struggles with the decision of squashing her spirited attitude and holding down a respectable but grueling job of physical labour, or the supposedly exciting but tainted life of a brothel girl.

The story is based on three real sisters from a poverty-stricken family. The author, Cathy Marie Buchanan was inspired by van Goethem’s story after watching a BBC documentary entitled The Private Life of a Masterpiece, which actually focused on the life of A Little Dancer Aged 14 (Little Dancer), aka Marie van Goethem. Buchanan, who used to dance ballet in her youth, describes that today “ballet is thought of as quite a middle-class pursuit … [but] back then the Paris opera was very much a place where high life met low life. It was a sort of gentleman’s club where mistresses were seen with noblemen.”

I did have a bit of an issue with the first person narrative. While the characters are truly what make the tale, I was torn between wanting to focus on Antoinette’s story and Marie’s inevitable tale, and also curious about their younger sister Charlotte, stuck in the background. However, with the first person point-of-view, the reader is stuck with one sister per chapter, jumping back and forth jarringly. Even Buchanan notes this competition, “As I began writing, Antoinette — Marie’s real life sister — demanded equal time and sisterhood became a dominant theme in the novel.”

Overall, despite these minor complaints, the novel is intriguing—a fast and satisfying read. The language and expertise Buchanan shows when writing about the ballet and Paris Opéra is solid. The story is heart-wrenching, sad yet beautiful, and will satiate readers who also enjoy the novels of Ami McKay and Marina Endicott.